Audubon Park

AP

Audubon Park: A Brief History to 1886

Today, the neighborhood that lies west of Broadway between 155th and 158th Streets in northern Manhattan bears no resemblance to the wooded vale that John James Audubon bought in 1841 and deeded to his wife, Lucy. The ancient elms and oaks that towered above dogwood and tulip trees on the hillside and the tall pines nearer the water, the streams that flowed through ponds and over a waterfall before joining the river, the enclosures where deer and elk mingled with domestic animals are long gone, displaced in stages of development and progress that culminated in the cityscape that exists today. Even the vale itself is mostly obscured by graded streets, building elevations, and the retaining wall that supports Riverside Drive, which at its deepest – near the spot where Audubon’s home once stood – is almost forty feet high. In place of those expressions of rural life, the Audubon Terrace museum complex and a series of apartment buildings have now claimed the tract longer than either Audubon’s home or the subsequent residential enclave that bore his name. However, just below the surface are subtle reminders of what once was, a patch of schist on 156th Street, panoramic views of the Hudson River and the Palisades from the Riverside Drive viaduct, the steep drop from the 155th Street plaza to the cemetery below, and especially the area’s peculiar footprint that refuses to adhere to the rigid grid pattern.

The urbanization of Audubon’s Arcadia was inevitable. Manhattan is a long, narrow island that by a quirk of events in the early 17th Century began developing on its southern end; eventually it found itself landlocked, the scarcity of land on the island rendering real estate speculation a profitable gamble and in the 19th Century, quite a respectable one.

Responding to a population that doubled every twenty years during the 19th Century, Manhattan did push northward up the island; the impetus – and often the impediment – was ever improving technology that increased construction and transportation potential. The constant lagger – which hindered middle class migration above 155th Street – was transportation. Successive improvements in mass transport expanded the city beyond the early jumble of named streets into an orderly, numbered grid, but technology and speed did not keep pace with population growth, so while transportation stalled in the 1870s and ‘80s, architects pondered centuries-old forms of shared housing – multi-generational households, boarding houses, and tenements – and synthesized a new multiple dwelling housing choice for the middle class. The apartment house, which blended privacy, light, ventilation, and above all convenience into an affordable horizontal living space, matured precisely at the moment a masterpiece of rapid transportation – the New York subway system – opened Washington Heights to New York’s middle class. The subsequent apartment house building boom along the route of the new subway absorbed Audubon Park, transforming it so rapidly, the Real Estate Record and Guide created a sobriquet: the Audubon Park Movement.

Remarkable as that sudden metamorphosis was, the subway was merely the catalyst for change. During the seven decades that spanned the appearance of Audubon’s farm and the disappearance of Audubon Park numerous technological, social, political, and familial events contributed to the “rapid transformation.” Those events, large and small, are the history of Audubon Park.

Minnie’s Land (click to return to top)

John James Audubon posthumously lent his name to Audubon Park, but he registered his 1841 land purchase, a fourteen-acre right triangle lying on 155th Street, in his wife’s name and called it Minnie’s Land in her honor – though Minnie was not her name. While the Audubons resided in Scotland during preparation of The Birds of America, Audubon and his sons Victor and John Woodhouse began using “Minnie,” a Scottish endearment for mother, to refer to Lucy Bakewell Audubon, so when Audubon deeded the farm to her, it became literally as well as nominally, “Minnie’s Land.” Although Audubon gave Lucy the property in partial compensation for the decades of separation and hardship she had endured during production of The Birds, registering the farm in her name was pragmatic. The depressed economy following the Panic of 1837 undoubtedly reminded Audubon of the Panic of 1819 that had left him bankrupt and homeless, so to safeguard Minnie’s Land against potential business failure and foreclosure, he deeded it for safekeeping to Lucy.

The Birds of America was a monumental undertaking that earned Audubon lasting fame as naturalist, painter, and American woodsman, but its original publication was costly and its profits small; however, the smaller lithographed version, The Octavo was cheaper to produce, affordable for a wider audience, and yielded higher returns that afforded Audubon the means to provide a permanent home for his family, one that could provide shelter as well as self-sufficiency. Audubon descendents recalled Minnie’s Land as an “estate,” but it was in fact a working farm carved out of the wooded valley just north of 155th Street. Minnie’s Land supported gardens, orchards, and livestock that supplied the Audubon family fruits and vegetables, eggs, milk, and meat; at their front door, the Hudson River – or North River, as it was then called – was a steady source of seafood throughout most of the year; and birds and small game that roamed the salt marshes along the river and woods bordering Minnie’s Land augmented what the family could produce for itself.

Audubon often voiced his distaste for cities, perhaps too often and virulently to be completely believable given the variety of guises he donned – ranging from dancing master, fiddler, and flautist to woodsman in buckskin clothing – to charm potential subscribers, but he had spent decades in urban areas, canvassing for subscribers, showing his paintings, and collaborating with engravers and colorists, so he understood that practically, as long as he was marketing The Birds, the Octavo, and his next planned work, The Quadrupeds of America, proximity to an urban center that offered contact with the wealthy individuals who formed his subscriber base was essential. Minnie’s Land was nine miles from the center of the New York City, close enough for Audubon and his sons to visit their office at 77 William Street often – daily when necessary. Although the Audubon house was secluded at the bottom of the vale near the river, the southeast corner of the property bordered Carmansville, a working-class village (with a general store, butcher, and druggist) that real estate speculator Richard Carman had begun developing a few years before the Audubons came to the area.

Dotted along the Kingsbridge Road – and more to the liking of the class-conscious Lucy Audubon than the carpenters and laborers who populated Carmansville – were the wealthy New Yorkers forming northern Manhattan’s gentry: Hickson W. Field lived south of the Audubon’s at his estate Woodland and to the north were Fanwood, home of James Munroe (nephew of the president), Oak Lawn, home of Montagnie Ward, and the large estates of James Gordon Bennett, owner and publisher of the New York Herald, John King, and lawyers Isaac P. Martin and Charles O’Conner. Northeast Madame Jumel’s mansion, formerly owned by loyalist Roger Morris, sat on a bluff overlooking the Harlem River. Eliza Jumel, who began her life in poverty and prostitution, first married a British officer, Colonel Peter Croix, and at his death married the wealthy Stephen Jumel, a French wine merchant who took her to Paris where she became a protégé of the Marquis de Lafayette and squandered a large part of Jumel’s fortune. Returning to the United States, she worked with Jumel to restore his fortune, which he left to her at his death. Like Audubon, who spent a lifetime fabricating events to hide the details of his birth and early years, Madame Jumel lived an invented biography, transforming her prostitute mother into an British aristocrat and her unknown father into a French naval officer.

Audubon Park before Audubon (click to return to top)

Before the Audubons, owners of the tract of land that would become Audubon Park had not found the area suitable for permanent habitation, nor had they contoured the land, diverted waterways, or humanized the landscape with buildings, cultivated fields and gardens, or roadways. The peripatetic Lenape, the Native American tribes that inhabited northern Manhattan and a large area in present-day Westchester, hunted Penadnic, as they called the heavily wooded area on the heights (including the future Audubon Park) and as excavations for apartment buildings in the early 20th Century revealed, they established a fishing camp on the banks of the North River near the foot of present-day 158th Street, but their balanced co-existence with the forest prevented their altering it with permanent dwellings or destroying the natural habitat that sheltered game they needed for food and clothing. When Dutch colonists began colonizing the Harlem plains they stopped short of the heights, which they called Jochem Pieter’s Hills in honor of an early settler, though they did venture there to hunt and to cut timber for the palisades that surrounded their homesteads – keeping cattle in and Native Americans out. Conflicting uses of Penadnic led to bloodshed.

Harlem’s Settlers Ascend the Heights (click to return to top)

By 1691, the Dutch settlers, whose determination to establish a permanent settlement had outlived the Lenape’s prior claims to the land, decided to divide the Common Land on Jochem Pieter’s Hills, drawing lots for the parcels. The allotment that included the future Audubon Park fell to Jan Dyckeman, whose son Gerrit built a stone house that sat on the southern end of the property close to present day 152nd Street and St. Nicholas Avenue. The vast acreage offered multiple flat and elevated areas that received ample sun and were more suitable for clearing and planting than the wooded vale on the western slope, which lay undisturbed. In 1767, after the property had been in Dyckeman hands for three-quarters of a century, Gerrit’s son John Dyckman (who Anglicized his first name and dropping an “e” from his last) divided and sold the farm. John Maunsell bought the southern portion and John Watkins bought the northern. Besides owning adjoining properties, the men were related by marriage. Their wives, Lydia Watkins and Elizabeth Maunsell were two of the six daughters of New York business man Richard Sitwell. The Maunsells lived in the stone house the Dyckemans had built near 152nd Street and Watkins built a house on the flat land at the crest of the heights not far from the Kingsbridge Road, close to present-day 157th Street, once again leaving the wooded vale on the western side of the island uncultivated just as the Lenape had before him.

Transition: American Revolution (click to return to top)

In the year preceding the outbreak of the American Revolution, John and Elizabeth Maunsell left the colonies. Maunsell sold most of his land in northern Manhattan and returned to his family home in Scotland, where he took a commission that kept him out of the conflict. The Watkins' neighbor to the north, Loyalist Roger Morris, abandoned his property and returned to England. Watkins was traveling at the outbreak of the war and could not return to the colonies until its conclusion. His wife Lydia, with her husband absent and one of her sons fighting with the Continental Army, moved to New Jersey to live with one of her sisters.

In September 1776, General Washington used the Morris Mansion as his temporary headquarters during the Battle of Harlem Plains, which was fought about a mile below the heights. Two months later, during the Battle of Fort Washington, the Continental Army established its second line of defense across the island at present-day 152nd Street and a third line of defense around 161st Street where it was well-positioned to cover a retreat across the wooded vale between the two. For decades afterwards, workmen digging in the soil (whether farming, excavating for buildings, or digging the subway tunnel) unearthed bullets, buttons, bits of crockery and metal, and assorted other reminders of those battles from the early days of the American Revolution.

The Watkins family returned to northern Manhattan after the Revolution and was living there when John Watkins died around 1787, with his property mortgaged to Maunsell, who was living with his wife in a house in lower Manhattan. He began foreclosure proceeding, but did not complete the process until 1793, when his nephew Samuel Watkins purchased the property at auction for £1000 and immediately sold it to his uncle for the same sum. Lydia Watkins was still living on the Watkins farm when Maunsell died, leaving his entire estate to his wife, Elizabeth. She built a house slightly north of her sister's. Lydia Watkins died in 1811 and Elizabeth Maunsell died in 1816. As she had no children, she left her extensive estate to her nieces and nephews. Three of the Watkins children inherited the farm, which they divided into three portions, Lydia Beekman taking the southern portion, Samuel Watkins the northern portion, and Elizabeth Dunkin the middle, which included the future Audubon Park. The three heirs must have leased their land during the next few decades, as they all lived elsewhere: Samuel Watkins, a physician, became a first citizen of Jefferson, NY (which later took the name Watkins Glen in his honor) and his two sisters lived in New York City.

Richard Carman: Real Estate Speculator (click to return to top)Around 1835, Richard Carman, who reportedly began his career as a box maker but had become a successful businessman with an interest in northern Manhattan's real estate, and James Conner, a printer whose fortune was based on a stereotype edition of the Bible that he produced for the American Bible Society, bought a large portion of the Watkins-Maunsell farm, apparently with the knowledge that the New York Board of Aldermen was looking for a suitable piece of land for a rural cemetery. Cemeteries within the city limits had exhausted their space Conner and Carman offered the city eight-six acres at $1400 an acre and seemed on their way to a deal, but after almost a year’s negotiations, the Aldermen selected an alternate site, leaving Conner and Carman with heavily mortgaged land that the New York Bowery Fire Insurance Company bought at a foreclosure auction. Conner abandoned land speculation altogether, but Carman jumped back into the market and began accumulating land once more On the same day that Audubon bought Minnie’s Land from the Bowery Fire Insurance Company, Carman re-bought a portion of the Watkins-Maunsell farm that he had lost three years earlier, absorbing it into Carmansville, the working-class village he was developing between 152nd Street and 155th Street. A year later he sold twenty-four acres east of 10th Avenue (present-day Amsterdam Avenue) between 153rd and 155th Streets to the Trinity Corporation for use as a rural cemetery.

Audubon Alters the Landscape (click to return to top)

When Audubon bought the wooded property that he and his sons developed into a farm, the Dyckeman and Watkins-Maunsell families between them had owned it for more than a century and a half, leaving it uncultivated and as wooded and untamed as it had been when the Lenape abandoned northern Manhattan. Ironically, as the first owner to begin shaping the land, diverting natural waterways, and building structures, Audubon, who promoted himself as the quintessential woodsman, naturalist, and detester of city life, began the sequence of events that would culminate in the urbanization of his Arcadia.

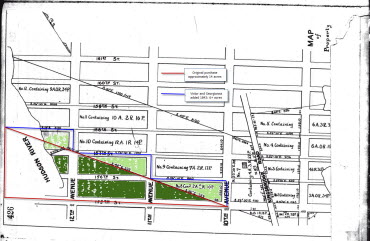

Immediately after Audubon registered the Minnie’s Land deed on October 1, 1841, his younger son John Woodhouse (who married Carolyn Hall, his second wife, on October 2) began work on the farm, first building a small house for the workmen high on the property and then constructing a house that contrary to the general practice on the Heights, sat on the lowest part of the property, near the river. Privacy seems to have been more important to the Audubons than fears of diseases associated with low-lying land or the potential for expansive views on the highest part of their property. Audubon’s original purchase was a fourteen-acre right triangle that began on the flat land at the crest of the Heights just north of Carmansville and slightly west of the Kingsbridge Road, at a point in the center of the intersection of present-day Amsterdam Avenue and 155th Street. From there, the southern boundary ran down the center of 155th Street to the high water mark in the Hudson where it turned ran straight up the river to a point between present-day 157th and 158th Streets. Then the triangle’s hypotenuse ran back ran along the old farm boundary the Dutch had established during the division of 1691 when Jan Dyckeman drew this lot, to its starting point in the center of 155th Street. About eighteen months after that purchase, Audubon’s son Victor added three parcels that “squared off” the original triangle, converting Minnie’s Land into three interlocked rectangles comprising a little less than twenty-four acres.

While Audubon and elder son Victor completed the Octavo and began work on The Quadrupeds, John completed building the main house, outbuildings, and a cottage for the coachman and his wife, constructed a road, and cleared the eastern portion of the farm – flat, higher, and thus receiving more sun throughout the day – for orchards and fields. By May 1842, the house was ready and the Audubons moved to Minnie’s Land where members of the family would make their home for the next four decades.

Transition: Minnie’s Land to Audubon Park (click to return to top)

Between April 1842 when John James Audubon arrived at his new home and January 1851, when he died, Minnie’s Land edged slowly towards Audubon Park, the enclave of mansions, a romantic suburb that would be its next stage of development. During that decade, John Woodhouse cultivated his fields and orchards, enclosed parts of the farm with paddocks for the Audubon’s quadruped specimens, and experimented with raising domesticated animals, his efforts on the farm helping to contain the family’s living costs

Church of the Intercession Emerges (click to return to top)

At the same time, the Audubons turned outward to the community around them. Always a gregarious family, the Audubons enjoyed a hospitable lifestyle that included social events with friends as well as long visits from relations and guests. In the mid-1840s, the Audubons joined Richard Carman, Montaignie Ward, Hickson Field, and some of the other residents scattered across the Heights to coax one of the priests from St. Andrews Church in Harlem to hold worship services in a building that Carman owned in Carmansville. By 1847, they had formed a permanent congregation and hired another priest from St. Andrews, the Reverend Mr. Abercrombie, as their rector.

Were the Audubon religious leanings really Episcopalian? John James Audubon was Catholic by baptism, though his bond with nature suggests his spirituality was more akin to Deism. Although Abercrombie presided over Audubon’s funeral, Audubon family recollections that he attended services at the Church of the Intercession are suspect. By 1847, when the church was completed and ready for services, Audubon had already passed into a “mental gloaming,” in which exposure to the formal liturgy of the Episcopal service could easily disorient him in the presence of neighbors, embarrassing the family. Lucy’s Audubon’s grandfather and father were followers of Joseph Priestly, one of the founders of Unitarianism, which she seems to have adopted early in life, even though she was buried with the rites from the Book of Common Prayer; but Lucy’s religious beliefs aside, the Episcopal Church was the church of the upper class, which surely would have appealed to her social aspirations – and more importantly, the wealthy parishioners were prospective patrons for the Audubon family business as well as links to further prospects.

In any case, the family quickly became active members of the congregation. John Woodhouse helped construct the first building that housed the Church of the Intercession and Victor played a prominent role in its administration. At the organizational meeting in December 1847, Victor and neighbor John Morewood were nominated to certify the proceedings in conjunction with the rector and then Victor was elected one of eleven vestrymen (the governing body of the church). At its first meeting, the vestry elected Victor its secretary and for the next three years, until he resigned from the vestry shortly after Audubon’s death (probably because the family business absorbed all his free time) his clear penmanship recorded the details of each meeting in the Vestry Minute Book. The other vestrymen clearly respected Victor’s business ability; in addition to electing him secretary, they elected him to the church’s building committee.

Trinity Cemetery and the Hudson River Railroad (click to return to top)

In May, 1843, just over a year after the Audubons moved to northern Manhattan, the first burial occurred in Trinity Cemetery. In the early years, mourners as well as visitors out for a Sunday-afternoon trip to the country arrived by public coach, private carriage, or on foot, but in December 1847, the Audubons and the other residents on Manhattan’s western shore deeded their riverfront to the Hudson River Railroad Company and by October 1849, trains ran up the west side of Manhattan on a daily schedule between the city and Peekskill. The railroad, with a station at the foot of 152nd Street, shortened the trip from Minnie’s Land to lower Manhattan to less than an hour and facilitated the next stage of transition from Minnie’s Land to Audubon Park.

Audubon Family's Failing Finances (click to return to top)

Had Audubon been aware of the railroad, he probably would have despised it, but by the time trains were running, he had sunk into senile dementia and his two sons were shouldering responsibility for the family business, hampered severely by the absence of Audubon’s charisma and single-minded focus. Reshuffling duties, Victor spent more time traveling to canvas for subscribers, which left him little time to paint or manage the office, so John managed the Beaver Street office and painted more, leaving him little time to farm. At a time when financial resources were weakening, the growing Audubon family was forced to purchase provisions that John and his farm hands had previously provided from their labor on the farm.

Victor’s surviving correspondence illustrates his clear understanding that the Audubon family’s business model – a subscription-based endeavor that depended upon patrons’ continued interest in each volume as the family produced it and their ability to pay each installment as it came due – was unstable and subject economic downturn, lack of a national currency, a banking system based on an exchange of notes (often at a discount) rather than checks, and continuous travel to deliver books and collect funds; so alternate sources of income were vital if the family was to remain finically stable. n 1849, financial desperation and a own thirst for adventure drove John Woodhouse to become second in command of an expedition to the California Gold Rush that Ambrose Kingsland, former New York City mayor and neighbor of the Audubons helped finance, but after harrowing adventures on the journey to California (when he assumed leadership of the remnants of the party), John arrived too late to stake a solid claim and eventually returned to Minnie’s Land no wealthier than he had left. Then, in the early 1850s, Victor and John speculated in Brooklyn real estate and took part ownership in a metal works foundry; Victor considered becoming a merchant; and John Woodhouse even attempted to secure subscribers for a Manhattan zoo, but their ventures were often ill-timed and competition was fierce, so none of these attempts to improve family finances succeeded.

Audubon Park Evolves (click to return to top)

Having exhausted other options, Victor – perhaps influenced by John’s brother-in-law James Hall, a successful merchant as well as friend and financial advisor to the Audubon brothers – convinced his mother and brother that since their land was not contributing to the family’s financial well-being as it had been when John was farming, they should rethink their options. Victor devised a three-prong scheme for Minnie’s Land: consolidate the family in houses along the river, sell land that would bring the highest values (mainly the flat land on the eastern portion of the property where John had planted orchards and tilled his fields), and build additional houses on the remainder, which they would lease and later, when real estate prices rose – as Victor was sure they would do – they would sell. Neither Lucy nor John was a willing convert. John desperately wanted to farm and Lucy wanted to retain ownership of Minnie’s – that is her – Land in the face of all obstacles. Audubon was mentally incapable of unifying the family with a focused, all-consuming vision as he had with The Birds, so the three bickering family members succumbed to dysfunction, with each championing a different cause. Nevertheless, as their fortunes sank further, Victor negotiated a temporary agreement with his mother and brother (though neither Lucy nor John ever fully relinquished their individual goals) and began to implement his plans.

Opening Minnie’s Land to new residents presented the logistical problem of keeping Audubon’s deteriorating mental condition as quiet as possible. Beyond public embarrassment, knowledge that Audubon’s mental capacity rendered him incapable of completing The Quadrupeds could be devastating to ongoing or new subscriptions. Even so, at the end of 1850, Victor was arranging land sales and house rentals while John Woodhouse supervised house construction, a venture that would bring new residents to Minnie’s Land. At the same time, both were still actively engaged in running all aspects of the family business: canvassing for new subscribers to the Octavo, painting illustrations for the yet-to-be-released Quadruped volumes, and overseeing all of the publication details for the volumes already in print.

James Hall took a house on the river at the northern corner of Minnie’s Land and Samuel Downer, an importer who had offices at 44 Beaver Street (directly across the street from the offices that the Audubons shared with Hall) and who was already living on the southern side of Trinity Cemetery, leased a house that John built in the yard where he had previously raised chickens – a moderate-sized structure that came equipped with its own ice house. While the Audubons sons built houses for Hall and Downer, they also built new houses for their own growing families, Victor’s just north of the original Audubon home and John’s north of that. The expenditure for new houses may seem ill-advised at a time when the family was struggling financially, but in 1850 the original Audubon house bulged at the seams with six adults, eleven grandchildren, and nine servants (no matter what the family’s financial circumstances, Lucy always maintained a cadre of servants), as well as frequent guests who might stay for one night or for weeks at a time. Victor, John, and Lucy apparently agreed that she would lease her house and then spend six months of the year with each of her two sons, thus providing Lucy and Audubon an income without forcing her to sell her house – her most treasured (and valuable) gift from Audubon.

How the mentally incapacitated Audubon would figure into these plans was not completely clear, but any potential problems ended when he died on Monday, January 27, 1851, one of those unseasonably warm days that Manhattan sometimes enjoys in the winter, though Wednesday when he was buried brought “a dull, cold cheerless sky, which threatened snow but finally dissolved in a dismal rain” leaving the streets “in a woeful condition.” Horace Greeley’s New York Daily Tribune announced Audubon’s death on page six and ran a half column obituary on page five that described Audubon as distinguished, illustrious, remarkable, and “possessed of an indomitable spirit.” Richard Gordon Bennett’s New York Herald ran an even longer article (Bennett was a neighbor to the north) that recounted major events from Audubon’s life (and perpetuating much of his invented biography). The Daily Tribune described the funeral as “wholly unostentatious and simple” and “largely attended by the friends of the family and other citizens.” The Rev. Mr. Abercrombie, Rector of the Church of the Intercession read the Episcopal burial service, after which the mourners trudged through the rain to a site on the southwestern corner of Trinity Cemetery not far from Audubon’s home to place his coffin, bearing “a plain silver plate with the following inscription: John James Audubon, Died January 27, 1851 Age 76 years,” in the family crypt.

Minnie Sells Some of Her Land (click to return to top)

In March 1851, barely two months after Audubon’s death, Lucy sold the eastern rectangle of Minnie’s Land – the block bounded by 155th and 156th Streets between 10th and 11th Avenues, where John had tended his fields and orchards – to Dennis Harris. The following November, she sold Harris and his brother William additional land and during the same year, she, Victor, and John transferred land to Edward Talman (whose wife, Delia, was sister to Victor’s wife, Georgianna), Louis Nagel, Wellington Clapp, and Henry Smythe, merchants doing business in lower Manhattan. Yet another merchant, Irish-born Alexander Munkittrick agreed to rent Lucy’s house once Hall vacated it and when it was available, he moved his wife, four children, and six servants to Minnie’s Land.

Like the other newcomers, Munkittrick was wealthy, belonged to the merchant class, and was an Episcopalian; he joined the Church of the Intercession and within a year was elected to the Vestry. Although Victor was the force behind selling Minnie’s Land, Lucy’s predilection for the well-educated, wealthy, and upwardly mobile seems to have determined who “got in.” Those who bought property, like Wellington Clapp (and Smythe), found that their deeds included a covenant forbidding any “dangerous noxious unwholesome (sic) or offensive trade calling or business whatsoever” including slaughter houses, cow stables, blacksmith shops, brass foundries, and soap, candle, varnish, or turpentine factories. The covenant would prevent industry and preserve the area’s rural character, but the Audubon brothers’ prime concern was that their houses were downhill of the other houses in Minnie’s Land and thus, highly susceptible to runoff.

New Neighbors, New Name… (click to return to top)

In the 1850s, as gardens, drives, and new houses displaced farmland and the natural topography that had drawn Audubon to the wooded vale more than a decade earlier, the newcomers began calling Minnie’s Land by the new name Audubon Park, a name change that occurred about the same time New Yorkers began referring to northern Manhattan as Washington Heights. The change reflected harsh reality: as the Audubon family sold and leased bits and pieces of Lucy’s farm, it literally ceased to be Minnie’s Land. Pragmatically, the Audubon name had sold subscriptions to the Birds and the Quadrupeds and now it would promote real estate. “Minnie’s Land” had been a personal, perhaps even half-jesting name, quite appropriate for the family farm, but Audubon Park suggested a refinement; the two-word combination evoked the naturalist, his beloved birds, and the natural – but increasingly cultivated – setting. In this instance, the Audubon brothers’ timing was impeccable. Though many urbanites found the city’s pace and its throngs of people exhilarating, others were drawn to the “romantic suburb,” an idealization of rural living that grew out of the English Romantic Movement at the end of the 18th Century. In America, Andrew Jackson Downing espoused the “romantic suburb” movement and advocated villas with tens of acres for those who could afford them and for those who could not, a smaller villa grouped with others in a park that featured non-linear streets, large lots, and houses that blended into the natural topography – precisely the transformation taking place within Minnie’s Land. Preserving the sylvan atmosphere, deeds included restrictions such as the ones the Audubons inserted in their agreements with Henry Smythe and Wellington Clapp.

Lucy later wrote that the name Audubon Park originated with “some of the gentlemen, friends of the Audubon family, who resided there after the naturalist’s death,” which is quite possible, but equally possible is that the model for Audubon Park was Llewellyn Park, a romantic suburb situated in the foothills of New Jersey’s Orange Mountains and though much larger than Audubon Park, was also a gated community that was a short railroad commute from Manhattan. Businessman Llewellyn S. Haskell developed and opened Llewellyn Park in 1853, just a year before the name “Audubon Park” first appeared in the New York Times – in James Hall’s obituary.

The British-born Hall died suddenly in May 1854 following a brief illness and after a Sunday afternoon funeral at Brooklyn’s Christ Church (attended by “friends of the family, and member of Excelsior Lodge, I.O. of O.F."), was buried in Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery. Hall’s grave sits on a hill in the middle of the cemetery; the inscription on his tombstone is now worn, but the location of his death is still clearly visible: “Audubon Park on the Hudson,” a euphonious phrase that combines the concept of the romantic suburb with British place names such as Stratford upon Avon. Hall may well have been among the gentlemen who honored Audubon with the name "Audubon Park," but he was also a clever business man and was probably equally influenced by the marketing potential of a romantic suburb a short train commute from the city and the example of Llewellyn Park.

…and Expansion (click to return to top)

The transformation from farm to romantic suburb was well underway by the time enumerator Roderick Knox, a house painter who lived in Carmansville, began counting residents of the Fifth Election District of the 12th Ward for the New York State 1855 census. From one Audubon household in 1842, comprising seven Audubons and a half dozen servants and farm workers, Minnie’s Land had grown to nine Audubon Park households comprising eighty-three individuals, of whom twenty-nine were servants and thirty-one were children between the ages of one and seventeen. The farm had disappeared under newly-built houses, the “crops” were individual gardens attached to the houses, and the menagerie of domesticated and wild quadruped specimens was reduced to chickens, ducks, and cows that provided fresh eggs and milk, though wildlife remained abundant in the neighboring woods and river. Although the repetitive city grid was already transforming the eastern side of 11th Avenue where Dennis Harris had divided his property into lots and resold the land he had bought from Lucy just a few years earlier, the Park remained undisturbed and the arrival of a new resident on January 1, 1857 – though unremarkable at the time – ensured it would remain so for decades to come.

The Grinnells Arrive (click to return to top)

In late 1856, George Blake Grinnell had leased Wellington Clapp’s house for three years and arrived in Audubon Park with his family New Year’s Day 1857. Blake Grinnell and his wife Helen had impeccable New England pedigrees stretching back to the Mayflower as well as social and political connections. Blake’s father had been a US Congressman for a decade, serving with Henry Clay, and Helen’s was a noted theologian, so they easily satisfied Lucy Audubon’s exacting standards for who would – and would not – be her neighbors. When he moved to the Park, Blake was a dry goods merchant in business with Levi P. Morton (future governor of New York and Vice President of the United States), but had begun his married life as a clerk in his cousin George Bird’s establishment, while living in a working class neighborhood in Brooklyn. In the course of a decade, he had worked his way up in business as well as in neighborhoods, moving from Brooklyn to West 21st Street in lower Manhattan and then to Weehauken, New Jersey before coming to Audubon Park. Helen Grinnell came from a strong Presbyterian background; the Reverend D. C. Lansing, her father, was famed for his oratorical and evangelical skill and founder of Auburn Theological Seminary, which he served as the first president as well as professor of Sacred Rhetoric. Despite the strong Presbyterian connections, the Grinnells eschewed the fledgling Washington Heights Presbyterian Church and followed the Audubon Park pattern, joining the Church of the Intercession, which by the mid 1850s was beyond capacity, prompting the vestry to appoint a committee “to confer with the Trinity Church Corporation in regard to building a chapel (in the cemetery) for the use of this church.” (More than sixty years later, Intercession would find a home in Trinity Cemetery, but only after a thirty-five year sojourn on the corner of 158th Street and 11th Avenue.)

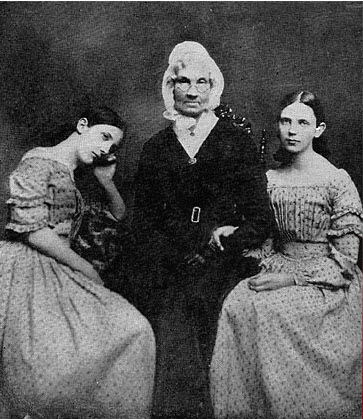

Lucy Audubon schooled her grandchildren in her bedroom on the second floor of Victor’s house where she was living and had begun admitting other neighborhood children for a fee, so according to stories the Grinnell’s eldest son George Bird later related, his parents sent him to “Madame Audubon” for lessons in letters and numbers, as well as ornithology and natural history. In his unpublished Memoirs, George wrote that Lucy Audubon ran her school because her “sons were in no sense moneymakers and had no notion whatever of the value of money. Madame Audubon, or ‘Grandma’ Audubon, as all the children called her, seemed to be doing for her sons and their families something like what she had been doing for her husband during much of the time since their marriage – earning the bread for the family.”

Ample evidence from Audubon family correspondence disputes Grinnell’s misconceived impressions of Victor and John Woodhouse, who worked tirelessly to support their families, as well as their aging parents. The suggestion that Lucy could have supported her sons, their wives, and thirteen grandchildren – not to mention the bevy of Audubon servants, who rarely numbered less than six – with the small income she earned teaching lacks credibility. Lucy schooled her many grandchildren – charging her sons by the pupil – because she wanted the independence of an income (albeit small), but even more because in mid-century New York educational options were limited. Having taught Victor and John their ABCs and numbers along with French, literature, and penmanship among other subjects an educated person would know in the 19th Century, Lucy taught her grandchildren as well. Over the next decade, she continually had a classroom, augmenting the Audubon children – and her pin money – with additional students from the neighborhood.

The Panic of 1857 (click to return to top)

In 1857, when the Grinnells moved to Audubon Park, Victor Audubon was bedridden, the result of an accident that injured his back and left him an invalid until his death in 1860 (shortly after the US Census enumerator listed him as “intemperance and insane” (sic), possibly as a result of medicinal use of alcohol or laudanum to relieve his pain), so John Woodhouse was left to run the family business alone. In August 1857, one of the 19th Century’s periodic panics struck the United States and set off a depression that left tens of thousands unemployed and further weakened the Audubon subscription business.

The Panic of 1857 also struck Dennis Harris, who had purchased the eastern portion of Minnie’s Land from Lucy Audubon in 1850 and then steadily accumulated real estate in the vicinity, dividing it into lots along the proposed but unopened streets, with the intention of selling them when prices reached their peak. Like Richard Carman, whose real estate speculation and development he appeared to be emulating, Harris was a self-made man. An ordained Methodist minister and a bricklayer by profession, he immigrated to the United States with his wife in 1832, traveling steerage. On board ship, he met Samuel Blackwell, an English sugar refiner who had recently suffered severe losses and sold his business to an employee, Samuel Guppy. Harris and Blackwell were fervent abolitionists (an interesting contrast to the English-born Lucy Audubon, who had owned slaves several decades earlier when she and Audubon lived in Kentucky). In New York, Blackwell found a position as a clerk in a sugar refinery and then convinced Guppy to partner with him in a new business, the Congress Sugar Refinery. Blackwell hired Harris to build the factory and then retained him as the factory foreman. Within a couple of years Harris had learned the sugar business, so when Blackwell was unable to pay his debts, he sold his share of the refinery to Harris and moved to Cincinnati where he convinced yet another sugar refiner that he had a secret process to refine sugar cheaply. Before he could fail in Cincinnati, he contracted malaria and died.

Meanwhile, Harris prospered in the sugar business – and odd occupation choice for an abolitionist, given that the Caribbean sugar plantations survived on slave labor – and built a second sugar refinery at the foot of 158th Street along with a wharf for docking the vessels that carried the refined sugar down the river to the city. Nearby were houses he and his brother William built on parcels they had bought from Lucy Audubon. Harris then began steamboat service, with William piloting the “Jenny Lind” that ferried passengers from 158th Street to lower Manhattan and as far Poughkeepsie in the north. Considering the sparse population on Washington Heights and the few potential passengers who lived in the vicinity of the 158th Street wharf, steamboat service seems an ill-timed venture, but it may have been cover for other activities. Harris’s Duane Street refinery was an active transfer point in the Underground Railroad and the steamboat, while a practical experiment in transportation, was more likely a surreptitious means of moving escaped slaves from the city into sparsely-populated Washington Heights before sending them on to the next safe haven closer to Canada.

Around 1854, the directors of the Webster Insurance Company scammed Harris and several other business men with offers of (worthless) stock and directorships in exchange for cash infusions into the company; Harris’s sum was $60,000. Though Harris recouped part of his “investment,” he lost about $16,000 and turned to his real estate for ready cash; fortunately real estate prices were relatively strong. He sold several lots on 155th and 156th Streets, including one on the corner of 155th Street and 10th Avenue to the Washington Heights Congregational Society, a church that had been holding services in a building Harris owned on 10th Avenue; the Society, which would eventually become Washington Heights Presbyterian Church, is today North Presbyterian Church located in the center of 155th Street between Broadway and Amsterdam Avenue.

Civil War Devastates Audubon Park (click to return to top)

Although Blake’s company, Morton, Grinnell & Co, (comprising Levi Morton, Blake and his brothers, William and Thomas) had suffered during the Panic, cotton trade was booming and the firm was back on its feet in 1860 when Wellington Clapp brought his family back to Audubon Park. In need of a new home and satisfied with the Park’s location, Blake negotiated a lease with John Woodhouse for the “house in the chicken yard” that the Audubons had originally built for Samuel Downer and later leased to Henry W. Johnson, an insurance broker and partner with the firm Johnson & Higgins. The Downer house too small for the Grinnell family and servants, so with Blake included additions to the house in the lease.

The Grinnell’s remodeled and expanded house, which they named “The Hemlocks,” was ready by May 1861 – and the timing could not have been more unfortunate. While workmen were finishing the new wing and interior modifications, Abraham Lincoln was sworn in as America’s sixteenth president and seven Southern states seceded; a month before the Grinnells’ moved to The Hemlocks, Fort Sumter fell, the American Civil War erupted, and the subsequent disruption of trade between the Union and Confederacy ruined Morton, Grinnell & Co, forcing the partners to declared bankruptcy and pay their creditors only 50 cents on the dollar. Although Helen Grinnell’s diary details temporary economies, Levi Morton and the Grinnell brothers Blake, William, and Thomas, were soon in business again – separately; Blake opened a dry goods store at 48 Park Place, Thomas became a merchant at 57 Murray, and William, who was married to Morton’s sister Mary, formed a new importing business with his brother-in-law at 53 Park Place, the former location of Morton, Grinnell & Co. All three of the new mercantile firms were well-positioned to bid on lucrative war contracts that would have put them on firm financial footing and possibly make their fortunes. By the end of the war, Levi Morton had become a banker and had moved from 17th Street to the more fashionable Madison Avenue, and all three Grinnells had turned to brokerage, an occupation that promised enormous capital returns during the industrial expansion in the late 1860s.

For the Audubons, the Civil War was far more severe than for their neighbors. The Panic of 1857 and Victor’s death had been disastrous for the family business and morale, but severing all trade with the Southern states, where the Audubon books were heavily subscribed, collapsed the Audubons’ finances. Then, John entered an ill-advised venture with Roe Lockwood, & Sons to produce a new edition of The Birds, which ended in litigation and the publisher placing a lien on the only unencumbered land the Audubons still owned. The decades-old Audubon family business ended in bankruptcy. John Woodhouse struggled to support his family, but his financial ruin had severely compromised his health and in February 1862, when a chill developed into pneumonia, he died.

Had the three Audubon women joined forces after John’s death, they might have devised a plan to salvage their finances. Each owned a house and land (albeit mortgaged), and at least three of the grandchildren, Harriet, Maria Rebecca, and Mary Eliza, were earning incomes as teachers; but John’s death left three separate Audubon households under two roofs and family dynamics prevented the heads of those households – Lucy Caroline, and Georgianna – from uniting.

Of the three women, the most unbending and disruptive to family harmony was certainly Lucy; compounding her stubborn self-absorption was her relationship with her two oldest granddaughters. Lucy had lost her own daughters when they were infants and was the only adult female in the family when John Woodhouse’s first wife Maria Rebecca Bachman died in 1840, leaving two baby daughters, Lucy (Lulu) and Harriet (Hattie). Though John remarried within months, Lucy raised Lulu and Hattie as her own daughters and favored them to the exclusion of her other grandchildren – setting up potential for family rivalries, not only among the children, but among their protective mothers as well. By 1862, when John Woodhouse died, Lulu had married and left Audubon Park, but the unmarried Hattie still shared a bedroom with her grandmother in Georgianna’s house, where both paid room and board. Complicating family dynamics was the matter of Lucy’s – that is Minnie’s – Land. Although Audubon had deeded the original fourteen-acre purchase to Lucy, Audubon land holdings had become unclear over the years. Victor and Georgianna had bought their own parcels – contiguous to Minnie’s Land – and Lucy and her sons had transferred land back and forth among themselves on several occasions, always with an exchange of cash recorded in the deeds. Despite the exchange of cash, Lucy maintained that she had given her property to her sons to finance their failed business ventures and that her life was made miserable by her “good deeds,” a resentment she seems to have transferred to their widows.

Within a few months of John’s death, Lucy, whose house was both leased and heavily mortgaged, moved to 152nd Street – Harriet in tow – where she boarded for awhile, wavering among several plans to salvage her finances, but determined to maintain ownership of her house and remaining property in Audubon Park. Lucy’s letters are full of complaints about her finances and detail her objectives: pay the mortgage and end the high interest payments, regain her house and inhabit it, and accumulate a substantial sum of money to invest as an annuity that would secure her and Harriet’s futures. Though she worried about Lulu’s hard farm-life with few servants, she trusted that Lulu’s husband Delancy Williams would provide for her. Lucy’s other eleven grandchildren gave her little concern.

Minnie Sells Her Legacy... (click to return to top)

In November 1862, William Wheelock paid Lucy $13,000 for the house he had been leasing on a yearly basis (the one originally built for James Hall) and the following month, Lucy began negotiations to sell Audubon’s original paintings for The Birds to the New York Historical Society. Her letters during the negotiations, which stretched over the next six months, veer between a self-pitying tone and savvy negotiation; Lucy had no qualms about the tactics she used to achieve her goal. With reminders that the purchase would assist “the helpless Widow and Orphan” – though technically an orphan, Harriet was now twenty-three years old and teaching school – Lucy claimed that “it was always the wish of Mr. Audubon that his forty years labor should remain in his country,” which is why she would give preference to the Historical Society over the British Museum, the King of Portugal, the Prince of Wales, or “friends in Philadelphia who are joining their efforts to possess these drawings.” She hinted that she must honor the Philadelphia friends in six weeks if they could raise the money (correspondence with George Burgess confirms that) and she waxed ironic: “It is somewhat singular that my enthusiastic husband struggled to have his labours published in his Country and could not; and I have struggled to sell his forty years labour and cannot.” After several months of negotiation, the Historical Society agreed to a price of $4,000.

…and Finally Her Land (click to return to top)

In 1864 as the Confederacy crumbled, real estate activity in Audubon Park accelerated. Blake Grinnell, who had recovered from his financial collapse at the outbreak of the war, bought The Hemlocks and William Wheelock purchased a house and land, but the inevitable was at hand. In March, her options exhausted, Lucy sold her beloved house and remaining parcels of Minnie’s Land to Jesse Benedict, a lawyer with the firm of Benedict and Boardman, who paid her $24,000 for the sale; $12,000 satisfied her mortgage. Caroline Audubon also sold her house and land, to Julia Gould Jerome, who bought it at auction in March for $15,000. In early May, both Lucy and Caroline closed their sales, satisfied their creditors, and left the Park. Several months later, Henry Smythe sold his house and property to Frederick Kirtland, who kept the house, but sold part of the large lot to Charles H. Kerner, owner and manager of the Clarendon Hotel on Fourth Avenue at 18th Street.

The flurry of real estate activity towards the end of the war, brought new faces to Audubon Park, but its footprint – the number of houses and their locations – remained static, and given the new residents’ wealth, occupations, and connections with New York’s upper crust, so did its social fabric. The most dramatic change was the Lucy Audubon’s departure. When Lucy sold her house – her final stake in Minnie’s Land – she had owned it twenty-two years, but lived in it less than half that time. She lost her tangible connection to Minnie’s Land, but her emotional attachment remained strong. Georgianna had several boarders in her home (including her sister and brother-in-law, the Talmans) and apparently was willing for Lucy to live there as well, but Lucy’s pride prevented her taking a room in “Mrs. V. G.’s” house and she steadfastly refused to pay $16 per week for a “cold room and many very disagreeables (sic) besides.”

Henry Smythe, the other departure had strong business and political connections and was a friend and one-time traveling companion of Herman Melville. Shortly after he left Audubon Park and moved to 5th Avenue at 42nd Street, he became Collector of the Port of New York, an appointee of President Andrew Johnson. In 1868, the House of Representatives recommended that Smythe be impeached, but since the Senate was coming to the end of a term and did not foresee adequate time for a trial, it ordered Johnson to remove Smythe from office. Johnson ignored the order, but the Senate had its revenge. Over the next few years, Johnson nominated Smythe as Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary (Ambassador) to Austria and to Russia, but, in an era of open warfare between the executive and legislative branches of the government, the Senate refused to confirm Smythe for either position.

Frederick Kirtland is one of the more elusive people to have lived in Audubon Park, but pieces of information gleaned from tax and census records confirm he was the social equal of his neighbors, though not as prolific in children. The 1856 Trow’s Directory listed him as a clothier with stores on both Park Place and Murray Street and living at the Collamore House, an upper-class residential hotel (and one of the progenitors of the apartment buildings that would eventually cover Audubon Park). By 1864, when the forty-eight-year-old Kirtland and his wife Cornelia moved to Audubon Park, he was paying taxes on income of $13,300 and four two-horse carriages. By comparison, his neighbor George Grinnell paid taxes that year on a one-horse carriage, a billiard table, and 226 ounces of silver plate, while Wellington Clapp claimed three carriages, a billiard table, and 213 ounces of silver plate. In 1870, the Connecticut-born Kirtland had a household that included his wife, his twelve-year-old daughter Eveline, two domestic servants, a cook, a seamstress, and a coachman.

Julia Gould Jerome, the new inhabitant of Caroline’s house, was the daughter of Phares Gould and recent widow of Addison Jerome, who had earned infamy on Wall Street for his audacious business dealings, lost his fortune in a speculative venture turned sour, and died, all within less a little more than a year. The savvy Jerome, who was uncle to Jennie Jerome, the future Lady Churchill and mother of Sir Winston, had transferred a portion of his wealth to his wife, which she combined with her own fortune to buy and refurbish Caroline’s house.

Infrastructure and Speculation (click to return to top)

During the Civil War, the New York state legislature continued financing public works and allocated funds for the construction and opening of a grand boulevard that would extend Broadway north from its terminus at 59th Street as far as 155th Street, splitting Trinity Cemetery in two parts and ending at a turn-around almost at the entrance of Audubon Park. Construction of the Boulevard proceeded slowly, in no small part because the notorious Tweed Ring, the political machine that ran New York City in the middle of the 19th Century, thrived on kickbacks, corruption, and minimal results. Tweed owned a large piece of property at 59th Street (now Columbus Circle) where the Boulevard joined Broadway and his cronies either owned or bought large parcels lining the proposed boulevard in anticipation of booming real estate development that would draw New Yorkers to the west side of the island. Rev. J. F. Richmond in his 1873 book, New York and its Institutions, 1609 – 1872, described the enterprise as “one of the later wonders of Manhattan,” and noted that “land is held at fabulous prices along its entire length.” Excepting the reference to land prices, Richmond’s rather poetic description ignores any possibility of graft or corruption and focuses completely on the advantages the new roadway would bring to horsemen.

We live in a fast age, and New Yorkers are a fast people; hence, it seemed intolerable to some that the law regulating driving at the Park should restrict every man to six miles an hour, and arrest summarily every blood who dared to disregard the rule. Nor was the private trotting course between the Park and High Bridge adequate to the demand. A great public drive, broad and long, where hundred of fleet horses could be exercised in a single hour, was the demand that came welling up from the hearts of thousands. One was accordingly laid out on the line of the old Bloomingdale Road, beginning at Fifty-ninth street with an immense circle for turning vehicles.

Looking back from the twentieth century, Robert A.M. Stern, Thomas Mellins, and David Fishman present a more accurate assessment of the project. “Though opened more or less on schedule, the Boulevard failed to become a prestigious address. Part of the problem lay...in the city's decision to pave it in gravel, a situation exacerbated by shoddy construction, which resulted in numerous craterlike ditches that frequently filled with water.”

Another problem was a lack of mass transit to Manhattan’s west side.

Public Transportation and Real Estate Development (click to return to top)

From the early 19th Century, public transportation and real estate development in Manhattan moved in tandem, progress in one spurring development in the other. Prior to 1820, when most of the population clustered at the bottom of Manhattan, crossing the city from river to river on foot was a journey of minutes and reaching the northern edge of the city not much longer, so public transportation was mainly inter-city, first by stage coach and later by train. As the 19th Century progressed and, social class – or aspirations to class – demanded that the work place and home be separated and preferably located in different parts of town, residential and commercial areas grew further apart; gone were the days when a respectable merchant lived in the floors above his shop.

Had New York City been rooted on the mainland along a river like many colonial cities were, development would have radiated outward, with each new layer of outlying residents being equidistant from the center, but New York City grew at the foot of a long narrow island on a natural harbor that separated it from the closest land masses (Brooklyn and Staten Island), so its most logical expansion was northward up the island. As long as New York was a city of merchants, the business center could only migrate a short distance north before it was impracticable, so northern expansion was mainly residential, and as soon as commercial endeavors moved into a residential area, residents who could afford to move did – usually further uptown beyond convenient walking distance to the city center. With access to private carriages or public hacks on demand, wealthier New Yorkers had no compelling need for public transportation, but the growing middle class, which inevitably followed the upper class to the periphery and side streets of the new neighborhoods, had no such luxuries and required transportation from home to office or shopping district and back again. Public transportation fit the bill.

Before Abraham Brower challenged the existing public transportation paradigm with omnibus service in the late 1820s, the primary means of overland transportation to or from Manhattan was stagecoach service, which was neither regular nor frequent. Brower’s omnibus “The Accomodation,” resembled a stage coach, but ran an established route on Broadway, adhered to a regular schedule, and charged an affordable fare of a few cents. Within a few years, teams of four or six horses were pulling more than a hundred omnibuses on regular service through New York’s streets and luring wealthier New Yorkers into new neighborhoods north of the established city limits. However, the omnibus wheels bumping over uneven cobbled streets riddled with potholes did not provide a comfortable ride and competition between the omnibuses and the horse-drawn hacks and cabs, as well as among the omnibuses themselves, grew raucous, with drivers vying for passengers waiting on street corners. The main losers in the battle were pedestrians, who literally took their lives in their hands trying to cross the street.

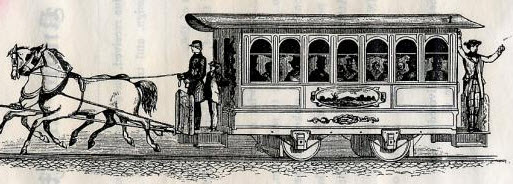

New competition arrived in 1832 when street railroads (or horsecars as they were commonly known in New York) began vying for passengers. Street railroad cars were similar to omnibuses, but ran on iron rails laid on the streets (sunk in them after about 1850), so a pair of horses could pull transport three times more passengers than an omnibus and do so more quickly. Street railroads pushed into neighborhoods further north, particularly on Manhattan’s east side, where the first horsecars connected lower Manhattan with Harlem in anticipation of a planned steam-powered railroad from there to Albany; by the beginning of the Civil War, Manhattan had expanded to Forty-Second Street.

Government participation in the omnibus and street railroads was limited to granting charters for routes (in exchanges for bribes and kickbacks) to private investors, who financed vehicles, horsepower, and any necessary construction, such as installing the rails for the street railroads. While this relationship was lucrative for both the politicians who awarded (or sold) the routes to the highest bidders and the private entrepreneurs who leased them and raked in profits from what amounted to monopolies, it proved to be one of two hindrances in the development of more advanced forms of mass transit – particularly development of the subway, which was far too costly for private investment alone.

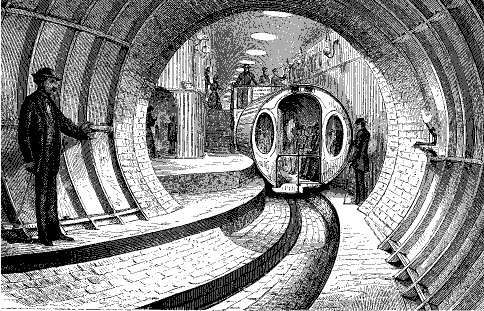

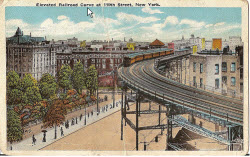

The other hindrance was technology. As early 1864, when London’s subway opened for business, forward-thinking entrepreneurs and real estate speculators in New York City understood that an increasing population – the result of waves of foreign immigrants, migration from rural areas, and a naturally expanding population – would eventually cover the entire island, but expansion could only happen when fast and relatively comfortable transportation could ferry the far-flung population on the long, narrow island, to the center of commerce and business in lower Manhattan and then back home again when the workday was done. Virtually all ideas for mass transit focused on railroads – the viaduct railway, the arcade railway (running on multiple levels simultaneously), the underground railway, and the pneumatic railway were all contenders, but technological problems in each variation hampered progress. And on those occasions when an entrepreneur put forth a viable transportation plan, the Tweed Ring flexed its muscle in Albany, tangling possible charters in bureaucracy’s red tape and preserving its lucrative deals with the street railroad owners and hack companies.

Annexation and Expansion in the 1870s (click to return to top)

In 1870, amid suggestions that the Tweed Ring had exhausted all possibilities for land speculation, sweetheart deals, kickbacks, and land speculation in Manhattan, plans to annex parts of Westchester County began in earnest and by the time a bill was ready for the governor’s signature in May 1873, the New York Times was ready to endorse annexation heartily, noting that northern Manhattan’s proximity and bridge connections to the proposed annexed district bound the two areas with security, health, and zoning concerns. With annexation, New York City could exert police, health, and zoning control over an area that was extremely close to Northern Manhattan and connected to it by several bridges; without annexation, the citizens of northern Manhattan would be subjected to potentially adverse conditions from lower Westchester County and have no governmental protection; growth in Washington Heights would suffer. As the century progressed, New Yorkers –particularly the New York press – continued to view Washington Heights as a desirable area for development, though at the time of annexation, when the notion of large multiple-dwellings built especially for the middle and upper middle class was first hold in Manhattan, no one foresaw that horizontal apartment living would eventually predominate in the Heights. Instead, developers and speculators north of 155th Street concentrated on single-family homes for the upper middle-class, like the ones that appeared amidst vacant lots on the streets branching off from the Boulevard.

Although the Boulevard had failed to promote real estate development on the upper west side as anticipated, the new roadway did provide another transportation connection between Audubon Park and the city and resulted in construction of a local landmark, the Gothic suspension bridge connecting the two sides of the cemetery. Above 155th Street, demands from a steadily – if slowly – increasing population grew strong enough to accelerate openings of cross streets as well as an extension of Boulevard to the northern tip of the island, but several decades would pass before 156th Street or 157th Street extended across the Boulevard into Audubon Park.

In the decade following the Civil War, Audubon Park’s footprint expanded to include the entire acreage west of the Boulevard between 155th and 158th Streets and encompassed property that none of the Audubons had ever owned. The Knapp family and Blake Grinnell annexed the strip of land on the southern side of 158th Street to the Park, Blake Grinnell taking the “near woods,” an irregular piece on the east, and the Knapps taking a long rectangle on the west, authenticating an Audubon Park footprint that had already begun appearing on Manhattan maps. On those rare occasions that the Park’s internal footprint – who owned which house and how much land surrounding it – changed, the new residents blended easily into the old. Audubon Park needed no co-op board or membership committee; its residents maintained the status quo by leasing, selling, or bequeathing their houses to relatives or close friends. Charles Francis Stone, who bought the house that once belonged to Victor Audubon, was a lawyer with the firm Davies, Stone & Auerbach and Levi Stockwell, who bought the house built for James Hall, manufactured the sewing machines his father-in-law Elias Howe had invented and that had come to prominence with the mass production of uniforms and other cloth supplies during the Civil War.

Blake Grinnell steadily increased his land holdings, purchasing the Kirtland house (originally the Henry Smythe residence) and the “near woods.” Then, he leased the Kirtland-Smythe house to his brother William, built a new barn in the line of 158th Street and demolished the old one, and expanded the Hemlocks with an eastern wing. Julia Jerome, whose family migrated with the seasons and appeared at society’s watering holes, temporarily leased her house and moved her family to West 20th Street after the war, but returned in the 1870s and lived there with her son Eugene and his wife, her daughters Fanny (Hildt) and Alice, six grandchildren, and six servants. Not physically a part of Audubon Park, but joined to it by shared class and wealth, the homes of William Foster, financier of the Ninth-Avenue El, and William A. Wheelock, who had first come to the Park when he leased (and then bought) James Hall’s house from Lucy Audubon, sat on the northern side of 158th Street, property that had been part of the Watkins farm some hundred years earlier.

French Roofs … (click to return to top)

Park residents old and new remodeled and expanded their homes with bay windows, ornamental ironwork, and in Blake Grinnell’s case, a new wing, and several, including Audubon’s house, succumbed to the mansard (or French) roof, which had first appeared in New York in 1852; twenty years later, a New York Times editorial caustically termed the continuing craze “mansard mania.”

Before it [the mansard roof] came, we were happy barbarians, livening in shapeless hovels of stone and mortar, tolerably fireproof to be sure, but woefully lacing in sweetness and light. But though they were contented with this groveling security, aesthetic souls still felt an aching void, an indefinable longing, which the plaster finals of Grace church could not satisfy, and which even the chaste splendors of the Fifth-avenue Hotel were powerless to quench. The Mansard roof appears, and everybody felt at once that it was the very thing we had all been waiting and wishing for – a sort of architectural long-lost brother. It was seen at a glance to be like those books which no gentlemen’s library should be without. No edifice of any sort seemed complete without it; it looked equally well on a model pig-pen or a life insurance palace…And, today, as every architect knows, to a gentlemen’s residence a Mansard roof is as indispensable an adjunct as a mortgage. (November 12, 1872, pg 4)

Whatever its artistic merits, practically, the French roof on the Audubon house maximized use of the third floor bedrooms that Lucy had used for children, servants, and guests she felt she could safely send to the top of the house. Figuratively, the roof was another manifestation of an 19th Century American interest in everything French: food, art, literature, French heels for women’s shoes, they all held fascination for Americans, particularly those whose accumulated wealth had increased their aspirations to rise in society. Even Helen Grinnell, whose diaries suggest she was a practical and unpretentious woman, headed her journal entries with French days of the week and month, a habit she suddenly instituted after a conversation with her sister-in-law who had just returned from Europe.

…but Not French Flats (click to return to top)

New York’s fascination with all things French stopped short of French flats, a term originally applied to multiple dwellings like the one Richard Morris Hunt’s created for Rutherfurd Stuyvesant on Eighteenth Street in 1869. Hunt, an American had studied art and architecture in Paris and brought back with him what he believed was a practical solution to New York’s housing shortage, a problem that had increased with population expansion following the Civil War. He had studied apartment buildings in Europe, where they were an entrenched housing form that dated from the Roman insulae. In European apartment buildings, various classes often shared buildings, stacked in floors with the wealthiest at the bottom and poorest climbing numerous flights of stairs to reach the attic floor. When Hunt introduced the Stuyvesant, a building of French flats, complete with French roof, middle-class New Yorkers, like their counterparts in every region of the country, exercised their freedoms of life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness in houses – free standing if possible, semi-detached row houses if not. Dividing a house among several families with each taking a floor, taking in boarders (or being one), and multigenerational families living under one roof were acceptable forms of shared dwellings in New York City; buildings specifically designed and built as multi-unit dwellings – except temporary residences such as hotels – were not.

On one end of the thought spectrum, New York’s existing model for French flats was the tenement house, such as the Dutch house that sat on the corner of the Boulevard and 157th Street across from Audubon Park, a multiple-dwelling that John Woodhouse Audubon built to house the men who worked at the sugar refinery at the foot of 158th Street and their families – their German ethnicity giving the house its name. Standing in a field with no adjacent buildings, the Dutch house had ventilation and light on four sides and was superior to its counterparts on Manhattan’s lower east side, dark and damp structures that were riddled with poverty, crime, and disease. Even so, as George Bird Grinnell recounts in his Memoirs, the privileged little boys in Audubon Park and the poor little boys who lived in the Dutch house lobbed names as well as stones across the fence that fronted Audubon Park in a youthful and not so innocent form of class warfare. On the other end of the thought spectrum, French flats suggested courtesans, assignations, and immorality. Laid out on a single floor with the distinct possibility of seeing a bedroom from the parlor, flats lacked the separation of public and private spaces families enjoyed in their multiple-story houses, and if families of different social class and wealth shared a building, how should unacquainted persons greet each other if they met in the common hallways or on stairs. Not surprisingly, the first tenants in French flat buildings were mostly single, widowed, or the adventurous; many were artists.

In July 1869, when only a handful of French flat buildings existed in the city, N.W.R. a homeowner in Mount Vernon, New York wrote the New York Times expressing an “Audubon Park” viewpoint, which many New Yorkers who have lived north of 155th Street in succeeding generations have shared: “within twenty miles of the City, in almost any direction, can be found hundreds of snug little houses which can hire for from $150 to $500 a year, or can buy (sic) them for $3,000 and upwards. These houses have more real comforts in them than the City “flat” can afford for four times the above figures.” When commuting to the city “is no more than to go from Fifty-ninth-street to Wall” and, most importantly, when one could not find a healthier place to live than Mount Vernon because “it is on the highest ground on the line of the New-Haven Railroad, which by the way, is the best managed and safest railroad leading” from the city, then “the thousands of young married men…living in boarding-houses or hotels at a cost of from $3,000 to $10,000 a year, (with little comforts)” should consider outlying areas. While hundreds of businessmen agreed with N.W.R. and commuted into the city daily, theirs was the minority view; thousands more preferred to live, where they worked, in the urban center. For them, French flats offered a new housing possibility.

But, even among those who considered the French flat a viable housing option, $5000 per annum for an apartment “capable of lodging six people,” was not competitive with the price of renting a full house. New York’s demand for French flats was low, but the supply was even lower. In March 1872, the New York Times (which endorsed the French flat concept when rents were proportional to the space leased), estimated that all the French flat buildings in New York would hold no more than fifty families. However, within very few years, as the French flat concept became more familiar and more popular, real estate speculators responded to demand with increased supply and prices became more affordable for the middle class – at the same time the cost of living continued to rise. Hundreds of “walk-up” French flats sprung up around the city, often in row-house neighborhoods; the smaller buildings occupied double-width lots, rose four to six stories (the greatest number of flights residents were willing to climb and the maximum height for fire protection), and displayed simple facades that mimicked the brownstone row houses that often surrounded them.

1873: A New Church, an Old Friend, and Panic (click to return to top)

Audubon Park was not immune to the growth affecting New York and the nation in the decade following the war and by 1873 plans were afoot in the Park and in the Grinnell family for both change and expansion. In the fall of 1873, after a trip west, George Bird Grinnell took over his father's business and Blake Grinnell retired. Towards the end of the summer, Lucy Audubon, who was approaching her eighty-sixth year, returned to New York for a visit that coincided with Delia Audubon's wedding and dedication of the new Church of the Intercession that now stood at the edge of Audubon Park, on the northwest corner of the Boulevard and 158th Street. A

The New York Times had reported on ground-breaking ceremonies a year earlier, when “many of the residents of Washington Heights assembled on the lawn of “The Hemlocks,” the residence of George B(lake) Grinnell,” where “the Sunday-school children, the congregation, invited guests, vestrymen, wardens, clergy, rector and Bishop” formed a procession and marched up the hill (no doubt singing a hymn) to consecrate the ground on which the new church would stand. With an expanding membership, the congregation was building a new edifice in anticipation of the population explosion all Washington Heights expected once the Elevated Railroad reached 155th Street. The building “in the florid Gothic style of the thirteenth century, cruciform, with transepts,” had a 180-foot high tower on the southeastern side “surmounted by a gilt cross of 10 feet” and a “turret and two clustered pinnacles” on the other side. At a construction cost approaching $89,000, it occupied eleven lots and contained adjacent audience, lecture, and Bible-class rooms that could be opened into one large assembly hall.

Panic of 1873 (click to return to top)

The promise of continued industrial expansion and prosperity, the family milestone of passing the torch in the Grinnell household, and Lucy Audubon’s triumphal return to her home and church in Audubon Park all screeched to a halt on September 18, when Jay Cook & Company failed, sparking the Panic of 1873. The stock market plunged, banks and brokerage houses failed, and the nation sank into another depression, while in Audubon Park, the collapse sent the Grinnell fortunes spiraling downward and the Grinnell family itself into exile for the remainder of the decade – effectively freezing the Audubon Park footprint until the end of the century.