Four Year Later: The Subway Opens (return to top)

Despite the extensive coverage of the Washington Heights groundbreaking in 1900, by the time the subway opened four years later, the events of that May day had already sunk into obscurity. Not a single news outlet mentioned the Washington Heights groundbreaking when Mayor McClellan [son of Civil War General George McClellan] inaugurated the subway on Thursday, October 27, 1904. Perhaps reporters were distracted by the Mayor’s antics. McClellan had the honor of starting the first train, but after a symbolic start at the "City Hall Loop," he was expected to turn the controls over to a qualified engineer. Instead, he refused and took the trainload of honored guests on a joy ride all the way to 103rd Street before the frightened engineer finally convinced him to hand over the controls.

The inaugural trip ended at the 145th Street station, one stop short of the 157th Street station where excavations had begun. Tracks, including the all-important, electrified third rail already ran to the 157th Street station, but lighting and tiling were not yet complete. Despite that, the 157th Street station opened temporarily two days later “to accommodate part of the throng bound toward and from the American League Baseball Park, where the Columbia-Yale football game was played.” Passengers traveling to the ball game found to their delight that the walk from the end-station to the playing field at Broadway and 166th Street was twelve blocks shorter than they had anticipated.

The up-town platform of the One Hundred and Fifty-seventh Street Station was the only one used. It is far from finished as to decorations, but had been cleaned nicely for the afternoon. The section down to One Hundred and Forty-fifth Street was unlighted except for passing trains, but from the car windows it was easy to see that regular operation thereabout was not far off.

The first “football express” train arrived at one-thirty, discharged passengers walking up the steps to the east side of Broadway and 157th Street across from Audubon Park, having a choice between walking up Broadway to the baseball park or walking one block east for a short trip on the Amsterdam Avenue street cars. Traffic in the afternoon moved fairly smoothly even with the increased numbers of passengers, a combination of sightseers who had delayed their first subway trip until the weekend, workers who had a half-day on Saturdays, and the “football express” crowd. After the game however, the local police and subway officials had their hands full when “a crowd of at least 10,000 people” left the playing field and began its journey south to the subway station. Reminiscent of the scene four years earlier on ground-breaking day, “Broadway, the Boulevard Lafayette, and the cross street were packed a hundred feet in each direction

It took twelve trains to get rid of the greater part of the crow, and even then there was a considerable number of people on the sidewalk waiting for a chance to get downstairs. Every train left the station packed, but the crowds were exceedingly good natured and the subway resounded with yells and college cries as the excited football enthusiasts whirled downtown.

For the next several weeks, the subway station at 157th Street was open “for the running of express trains on Sundays only,” but regular service to the 157th Street station began December 4, 1904,”shortly after noon,” with some passenger riding up to the station just “for the experience of traveling a few blocks further northward in the tunnel” than they had been able to do before.

Audubon Park: Where Excavations for the New York Subway Began

Webmaster's collection

A Near Miss (return to top)

Although a subway route under Broadway to the top of the island had been the backbone of rapid transit plans as early as the Steinway Commission’s 1891 proposal, when the Rapid Transit Commission (RTC) delivered contracts to New York City Corporation Counsel John Whalen in May 1897 – contracts that would not be valid without his signature – the citizens of Washington Heights had reason to worry about the Commission’s priorities. Just a few weeks earlier Governor Frank Black had signed legislation creating the consolidated City of Greater New York, an entity that would commence on January 1, 1898 combining Brooklyn, Queens, and Staten Island with Manhattan and parts of the Bronx, an exciting prospect, but one that raised concerns about public projects throughout Manhattan, particularly in Washington Heights. As the New York Times reminded its readers in January, 1897:

When consolidation has been effected and three million people look to the Government that will have its home in or near the New York City Hall for the execution of public works that will promote their comfort or convenience, there will be urgent demands from Kings, Queens, and Richmond in addition to the modest requirements of our own people in New York.

Rumors that the RTC intended to run the subway tracks only as far as 59th Street, using the savings for a tunnel to Brooklyn, sent upper Manhattan into a tailspin. By the end of January, 1897, landowners along the upper west side, following a model

Monday morning, May 14, 1900, Washington Heights buzzed with activity. Well before dawn, workmen had begun assembling near Broadway and 156th Street, and by “10 o’clock fully 200 men were lying along the green roadway opposite Audubon Park,” representing the nationalities and races that populated the world’s melting pot, Irishmen, Italians, Australians, South Africans, African-Americans, running the gamut from unskilled laborers to experienced miners. A few blocks east, at 458 155th Street, shortly after sunrise lawyer John Whalen woke to “a hammering that sounded as though a hundred men were assailing his home from all sides with hammers.” Grabbing his old navy revolver and rushing outside to confront his assailants, he found a group of exuberant neighbors decorating his house with flags and bunting. Once finished, they turned to their own, not satisfied until all the houses in the neighborhood “bloomed into waving color.” An hour or so later, children in the public school fidgeted their way through a half-day of lessons, with Misses Norcott, Walsh, and Holley trying to maintain order, themselves distracted by last minute preparations for what promised to be an eventful afternoon. Further south, at Amsterdam Avenue and 138th Street, children in the Hebrew Orphan Asylum Band spent the morning polishing their instruments in readiness for a march up the hill to 156th Street where they would play an important part in the afternoon’s exercises. In Audubon Park, by mid morning the cadre of servants in the Grinnell and Martin households were busy preparing for an early evening reception at the Grinnell villa – invited guests only – while Newell Martin and former police inspector Thomas McAvoy, co-chairs of a “Committee of Arrangements,” discussed last minute preparations, then walked up the hill to oversee construction of a grandstand at 156th Street and Broadway, directly in front of the main entrance to the Park, supplying temporary employment for a few of the waiting laborers. By mid-day, the broad macadam plaza where the Boulevard Lafayette broke off from Broadway at 156th Street began filling with a spirited crowd, come to witness progress. May 14th, 1900 was subway day on the Heights and everyone on the Heights had good cause for jubilation.

established several decades earlier by the West Side Association, incorporated as The Riverside Drive Extension Association of New York City “to promote the development of that part of the territory included in New York City, which lies north of One Hundred and Twenty-Second Street, south of One Hundred and Eightieth Street, and west of the Boulevard and Eleventh Avenue, to cause surveys of the territory to be made, to procure streets, roads, avenues, parks, or public places to be opened and laid out, grades to be established, and viaducts, causeways, or bridges to be constructed, etc.” The association had five directors, each with extensive property interests along the Hudson north of 122nd Street: Robert J. Hoguet, Francis M. Jencks, Charles V. E. Gallup, and representing Audubon Park, Newell Martin (married to the youngest Grinnell sibling Laura) and William Milne Grinnell, who also served as secretary. While the association’s name left little doubt that its primary objective was the extension of Riverside Drive northward from Grant’s tomb, its strong political connections positioned it as a notable addition to the “twenty social and political organizations, representing several thousand citizens” that united under the rather ungainly name of the “Committee on Public Opinion and Rapid Transit Agitation.” Among the Grinnells' important connections were former-Senator Charles L. Guy and former NY Govenor Levi P. Morton. (Morton, who was also a former Vice President of the United States, had been George Blake Grinnell’s business partner before the Civil War, his sister Mary was married to Blake’s younger brother William, and Blake Grinell’s third son was named Morton in his honor.)

The Committee's trump card was Corporation Counsel John Whalen, Washington Heights resident and property holder, a man with the ofifcial position to prevent the rapid transit controversy from dragging on for years – as the battle over the Riverside Drive extension to 158th Street did. Whalen disagreed with the proposal “before the Rapid Transit Commission to amend the plans already adopted by providing for an extension to Brooklyn and other parts of Greater New York,” and opposed “mixing other tunnels with the original underground road, for which the Rapid Transit Commission practically was created.” He stated flatly that “the enlargement of the city” had no bearing on Manhattan’s rapid transit plans, which Manhattan’s voters had decided by referendum before consolidation took place. Whalen had no intention of signing any contracts that would short-change Washington Heights, where he had friends, family, and most importantly, property.

Corporate Counsel Whalen’s Waiting Game (return to top)

For eighteen months the unsigned contracts sat on Whalen’s desk while he voiced concern for the newly consolidated city’s debt (a level established by the state legislature) and for the RTC contracts which he believed should “be amended to comply with the labor law of 1899,” but his chief reason for dragging his feet was his conviction that the only way to ensure the subway ran into Washington Heights was to begin construction at 155th Street and work north and south from that point simultaneously. Whalen set his demands to the RTC high, leaving himself some negotiating room, and finally achieved a satisfactory compromise: construction would begin at 155th Street and in lower Manhattan and then proceed north from both locations.

As a bonus, actual excavations for the subway tunnel would begin during a Washington Heights ground-breaking, and not at the official City Hall ceremony. Leaving no wiggle room for the RTC, the only contracts Whalen executed before the Washington Heights groundbreaking, were those “obtained by L. B. McCabe of Baltimore, for the construction of the two sections” of the subway extending north from 133rd Street. Laughing off rumors that “the delay was due to some hitch in the bonding of the sub-contractors,” the chief contractor for subway construction John B. McDonald (who was also Whalen’s cousin) bluntly stated that “the construction company had purposely delayed the beginning of work on the lower sections in order that the first start might be upon the northern section of the route,” at 156th Street directly in front of Audubon Park.

So on the morning of May 14, 1900, six weeks after the official ceremony in front of City Hall – a grand affair celebrating the consolidated city of Greater New York and the technological feat that would bind its residents by underground railway – Washington Heights prepared to enact its own ground-breaking, a community fete, combining county fair and fourth of July, with a bit of Decoration Day thrown in for good measure. Reporting the coming events a day in advance, all of the New York newspapers pounded home the significance of the Washington Heights festivities.

Actual excavation of the rapid transit subway will begin to-morrow afternoon. Nominally there have already been two beginning (sic) of work on the tunnel. These were when the Mayor some weeks ago formally dug the first spadeful of earth in front of the City Hall, and when, a few days later William Barclay Parsons, chief engineer of the Commission, wielded the first pick at Greene and Bleecker sts., when James Pilkington started to lower a sewer that lay in the path of the tunnel route.

But to-morrow the excavation proper of the subway will be begun, when L. B. McCabe, who secured the sub-contracts for constructing Sections 18 and 14. extending from One-hundred and-thirty-third-st. to Hillside-ave. will start digging at One-hundred-and-fifty-sixth-st. and Broadway.

Subway Day on the Heights (return to top)

As morning wore into a brilliant and unseasonably hot afternoon, the citizenry of Washington Heights began arriving from “Fort George, Spuyten Duyvil, Inwood, Marble Hill, Dyckman’s Meadows, Carmansville and other points [in] hundreds of conveyances” – their horse-drawn vehicles contrasting sharply with the electrified subway they were coming to inaugurate. Revelers had multiple choices. Anyone standing on the Gothic bridge that spanned Broadway and connected the two sides of the Trinity Cemetery could watch carriages coming up the hill from the south and then turn around to see the grandstand one block north. Picnickers spread blankets on the grassy plot in the eastern side of Trinity Cemetery near the seven-year-old Audubon monument, a spot the Church of the Intercession would occupy more than a decade later. A climb into one of the oaks or elms on the eastern side of Audubon Park provided a view over the top of the crowd and the bell tower on the south east corner of the Church of the Intercession at 158th Street and Broadway must have lured one or two parishioners willing to climb the many stairs to secure a perch more than 100 feet above the proceedings, though the church’s Rector, the Reverend L. H. Schwab, would more likely have taken a seat of honor with the other neighborhood clergymen. No one could get too near the grandstand however, because a cordon of policemen surrounded it, guarding a stone placed in the center of Broadway, the spot where Corporation Counsel Whalen would begin digging during the ceremony.

At 2.00 p.m., while the crowd was jockeying for position and the Misses Norcott, Walsh, and Holley were giving last minute instructions to their phalanx of students “the police boat Patrol with Mr. Whalen and 100 guests aboard left Pier A for 155th Street,” stopping for additional dignitaries at the Atlantic Transport Line pier before racing up the Hudson neck-in-neck with the steamer Ben Franklin. Winning by “a quarter of a length” the Patrol pulled up to the pier at the foot of 155th Street just before 4.00 o’clock where “a crowd of several hundred people, the band of the Hebrew Orphan Asylum and a platoon of police” had gathered. A "detachment of the Louis Wendel Battery” had stationed itself further up the hill at the intersection of 155th Street and Broadway, two cannons ready for a “salute of seventeen guns.”

When the Patrol docked, its “rapid fire one-pounder mounted in the bow fired a salute at such close quarters that some of the unmilitary guests nearly had their ear drums shattered.” At the top of the hill, Wendel’s Battery returned “the police boat’s salute with interest.” Then, while the band saluted Corporate Counsel Whalen with “Hail to the Chief,” Mayor Van Wyck, August Belmont, Chief Engineer Parsons, contractors McDonald and McCabe, and an assortment of Commissioners representing the police department, fire department, post office, coroner’s department, and every other city department that could sacrifice a commissioner for the afternoon, formed themselves into two columns and marched up the steep 155th Street, or as the New York Herald ungenerously quipped “heavyweight politicians toiled up the hill.”

Reaching Broadway, the procession made a smart left face, processed northward, and mounted the platform in the center of the intersection. Then seven hundred children, three hundred from the public school and four hundred from the Orphan Asylum, “countermarched past the grandstand and were reviewed by Mr. Whalen and Mr. McDonald,” after which Chief of Police Dewey, dressed in a new gray spring suit, formed them into lines for the singing of the "Star Spangled Banner." Apparently determined to be heard at City Hall nine miles south, the children sang and waved flags, the Hebrew Orphan Asylum band played “with extra fervor,” and the crowd roared with “cheers for rapid transit.” After the children and band obliged the crowd with “Columbia” and “The Red, White, and Blue,” Newell Martin, the master of ceremonies for the afternoon, introduced Chief Engineer Parsons, whose brief remarks expressing “the hope that the work so auspiciously begun would be pushed to a speedy conclusion and that Washington Heights would thus be closely linked with lower Manhattan” roused the crowd to more enthusiastic cheers.

Speeches, Music, and Three Cheers for Rapid Transit (return to top)

Mr. Parsons then introduced Corporate Counsel Whalen, who received the longest and loudest cheers of the afternoon. Whalen recounted “the years of discouragement that had been endured by citizens of Washington Heights” while they waited for the expansion their part of the city deserved and then thanked the RTC for honoring Washington Heights by “beginning the actual work of tunnel construction in their neighborhood.” He also exhorted the crowd to agitate for extension of the four-track system through Washington Heights, a wish the RTC did not fulfill, though it did oblige with a single “express” track as far as 145th Street.

As a brief intermission in the oratory, the school children, who no doubt had whispered and tittered their way through the speeches despite the watchful eyes of Misses Norcott, Walsh, and Holley, sang “America” and then the Master of Ceremonies introduced the chief contractor for the northern section, John B. McDonald; apparently a shy man of few words he “had quietly slipped out of the crowd and was making for a clump of trees” in Audubon Park when “a committee of three chased him and escorted him back to the grandstand.” The Sun recorded McCabe’s twenty-seven words thanking the crowd for its ovation and promising to get to work, “without delay.” (The Herald correspondent heard and recorded thirty-seven words, the sentiment virtually identical to what the Sun reporter had heard.)

The last speaker was Manhattan’s borough President James J. Coogan, a local property owner whose name survives in Coogan’s Bluff, where for decades thousands of fans enjoyed baseball games (Giants, Yankees, and Mets) without the inconvenience of paying admission to the stadium. Not a man to forego political opportunity, Coogan “made no effort to escape” and apparently appropriated McDonald’s unused speaking time. Congratulating Tammany Hall for rapid transit, extolling the Democratic administration of the city for rapid transit, and reiterating that rapid transit was “of vital importance to Washington Heights,” and would proceed without delay, he reminded the crowd – as if anyone could still be ignorant of the fact – that except for “the untiring efforts of our Corporation Counsel, who would not sign the contract unless the work for this section was placed therein, we would not to-day be witnesses to the greatest boom Washington Heights has yet received.” As the crowd cheered itself hoarse for Whalen and rapid transit, the band of the Orphan Asylum played John Philip Sousa’s rousing march “The Stars and Stripes Forever” while the dignitaries climbed down from the grandstand and processed to the middle of the intersection of Broadway and 156th Street to the stone marking the spot where Whalen would begin excavating the first rapid transit tunnel.

Breaking Ground: Turning the First Shovel of Earth (return to top)

Prior to the official groundbreaking in March, city workmen had removed “5 by 7 feet of flagging from the walk in front of the centre door of City Hall,” then dug a trench about three feet deep, taking the earth away and replacing it with “nice, clean, loose, and easily handled official dirt” for the Mayor and other officials to remove during the ceremony later in the day. Not so in Washington Heights. While the band played and the crowd “made the air vibrant with their cheers,” Whalen removed his coat and hat, gave them to a bystander, and then “swung a heavy iron pick [the Herald reporter believed it was silver] that was handed to him by L. B. McCabe, the subcontractor for the section, and for a moment or two dug away with an energy that started the perspiration at every pore.” The crowd, unable to contain its enthusiasm or restrain its wit, encouraged him with pithy remarks like “Good for you, you’re worth $2 a day” and “You’re a little too stout, but you’ll train down with steady work.”

Whalen labored sufficiently to dislodge “enough earth in the middle of the roadway to fill the silver loving cup” a group of his grateful neighbors had presented him a few nights previous at a dinner in Sherry’s restaurant, an evening that began with dinner, followed with speeches, and ended with recitations from Shakespeare by Fire Commissioner John J. Scannell. The Times, reporting that event in glowing terms, remarked that “none of the Rapid Transit Commissioners was present” and hinted to its readers that the reason might well have been Whalen’s defiance of the commissioners by refusing to sign the RTC’s approved contracts unless work began on the “northern and southern sections simultaneously.” The Daily Tribune, taking a more jaundiced view of events, reported “one of the most remarkable dinners and presentations ever witnessed” in New York City and wondered that anyone could honor Whalen with “a loving cup for his ‘great public services’” when it was “perfectly well know to every one with a memory that Corporation Counsel Whalen never approved of the Rapid Transit Tunnel Scheme till Richard Croker [the leader of Tamany Hall] told him to,” but by the time of the ground-breaking festivities, the Tribune had adopted the party line and reported that Whalen had “urged upon the Rapid Transit Commission the desirability of starting the work of digging the tunnel in the northern part of the city simultaneously with the lower sections,” earning himself the honor of striking the “first blow with the pick.”

As Whalen dug a hole “to a depth of about three inches” below the macadam pavement, Newell Martin produced the silver loving cup – made by Tiffany – and “Whalen shoveled the dirt into it with a silver spade, presented just in time by the William L. Marcy Association” a Democratic organization led by Thomas McAvoy (co-chair of the Committee of Arrangements and instigator of the early morning decorations at Whalen’s house). Whether Whalen ever planted a “rose bush and a number of shamrocks” in the loving cup as the presenters had planned is a bit of history lost to posterity.

What is not lost is that as soon as Newell Martin filled Whalen’s loving cup with Broadway earth, a dozen workmen, hired from the group that had assembled before dawn, lined up across the roadway and began digging a trench thirty feet wide, the width of the tunnel from wall to wall – while Whalen hunted for the man who had been holding his hat and coat. Once the dignitaries had cleared out of the way, the cordon of police stepped aside so that souvenir hunters could rush forward to collect mementos of the day.

The official Washington Heights groundbreaking complete and excavations for the tunnel underway, a hundred invited quests walked down the hill to the Hemlocks for a dinner with hosts George Bird Grinnell and his brother-in-law Newell Martin, more speech-making, and no doubt more of Commissioner Scannell's recitations from Shakespeare. On Broadway, the remaining celebrants began dispersing to their homes in Fort George, Spuyten Duyvil, Inwood, Marble Hill, Dyckman’s Meadows, and Carmansville, many bearing a few pebbles or a handkerchief full of earth, remembrances of subway day on Washington Heights.

Although the community festivities on the Heights might have lacked the grand pageantry of the official groundbreaking in front of City Hall, the New York Sun was sufficiently impressed to report the next morning that the festivities in northern Manhattan had “made the recent tablet-laying in front of City Hall seem like a country cattle show on a rainy day.” While New Yorkers read that and other accounts of the preceding day’s festivities, Contractor McCabe left the house in 157th Street, where he and his brother were living until their leased home in Audubon Park was put in order, and walked to the newly-dug trench at 156th Street where thirty of the men who had lined up for jobs the previous morning began subway excavations in earnest.

Subway excavations at 156th Street and Broadway, 1900

Sources: (return to top)

NY Evening World, May 14, 1900, p 1 and p 8 “Work on the Tunnel Underway at Last”

NY Daily Tribune, January 7, 1900, “Whalen Opposed to Tunnels”

NY Daily Tribune, May 10, 1900, p 4, “Whalen Gets a Loving Cup”

NY Daily Tribune, May 14, 1900, p 1, “Real Tunnel Work Now”

NY Daily Tribune, May 13, 1900, p 4, “To Begin the Subway”

NY Daily Tribune, May 15, 1900, p 1 “Whalen Begins Tunnel”

NY Daily Tribune, October 30, 1904, “At One Station, 15,000”

NY Daily Tribune, December 5, 1904, p 3 “Subway to 157th-St. Now”

NY Herald, May 15, 1900, “Tunnel Begun on Washington Heights”

NY Sun, May 15, 1900, p. 2, “Tunnel is Really Begun: And Washington Heights Does Honor to the Event”

NY Times, January 29, 1897, p 6, “The Riverside Drive Extension”

NY Times, March 25, 1900, p 2, “Rapid Transit Tunnel Begun “

NY Times, May 10, 1900, p. “Loving Cup for Mr. Whalen”

NY Times, May 15, 1900, p. 2 “Ground Broken for the Big Tunnel “

NY Times, October 30, 1904, p 12 “Northern Subway Limit Twelve Blocks Further”

NY Times, December 5, 1904, p 7 “Subway Alarm System Tested Three Times: New Up-Town Station Opened”

NY Times, November 13, 1951, “Letters to the Times”

Ceramic station marker

157th Street Station

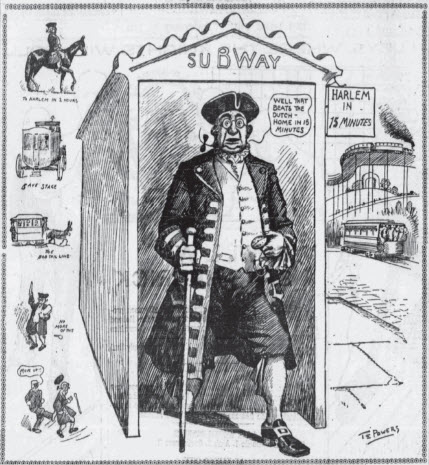

Subway humor , Opening Day 1904

(Left) Father Knick: "Bless Me! To Harlem in Fifteen Minutes At Last!" (T.E. Powers)

(Right) Capitalizing on the new sensation of speeding along at 25 mph underground.

Return to your walk . . .

Funded by the Audubon Park Alliance

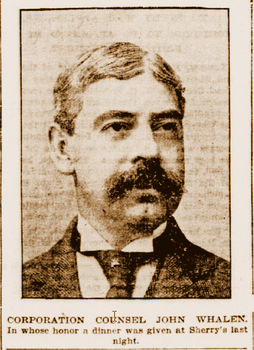

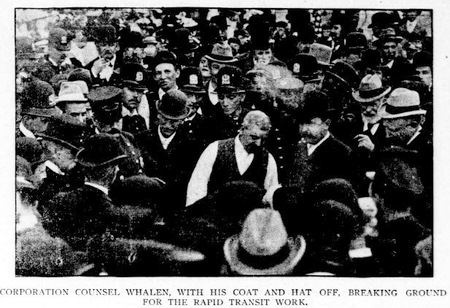

Corporation Counsel

John Whalen

Washington Heights resident

and property holder,

local hero who insured the subway came to the Heights,

wielded the pick that broke ground beginning excavations for the subway tunnel.

(Photo: NY Daily Tribune, May 10, 1900, page 4)

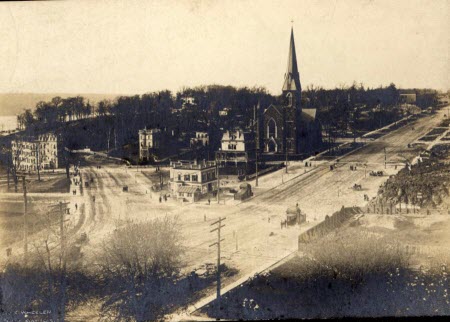

Broadway and 157th Street

Subway entrance in foreground,

Church of the Intercession in background, its steepled bell-tower a choice viewing spot for the groundbreaking two blocks south.

(This photo is from 1905, after the subway was complete;

downtown entrance to the 157th Street station is in the center foreground.)

Bridge over Broadway near 155th Street, connecting the two halves of Trinity Cemetery (removed in 1915)

John Whalen, center, breaking ground at 156th Street

and Broadway,

New York Tribune, Tuesday, May 15, 1900